Larry Lujack would have hated the vast public outpouring of love and affection that followed news of his death Wednesday after a very private, yearlong battle with esophageal cancer.

And he would have hated stories like this that called him one of America’s greatest radio personalities of all time and Chicago’s preeminent disc jockey for the ages.

Because true as it was, that's not what mattered to him.

“Larry didn’t want an obituary filled with people saying what a great guy he was and how talented he was,” his wife, Judith, told me after confirming his passing at age 73. “He was more than that. He was more than a jock. He was more than an employee of WLS. He was a truly amazing, caring, wonderful human being. He didn’t want to be known by the awards he won. He just wanted to be remembered as a person who cared about people — about children — and really tried to do things to help them.”

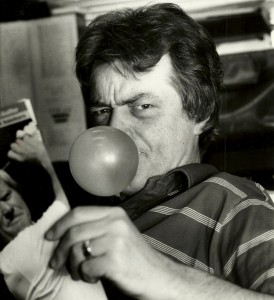

Though pretty much out of the limelight for more than 25 years and enjoying retirement in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Lujack left an impression on Chicago that endures to this day. Mere mention of “Ol’ Uncle Lar” from the “Animal Stories” bit he played to perfection with Tommy Edwards still conjures fond memories for hundreds of thousands of loyal fans.

His legacy also lives on among the countless broadcasters he influenced and inspired. The next time you hear Rush Limbaugh rustle a paper on the air or puff himself up with mock grandiosity, remember who did it first — and did it better.

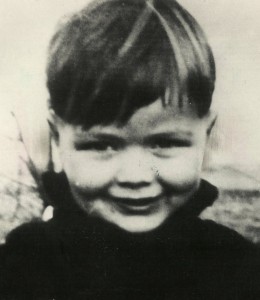

Born Larry Lee Blankenburg in Quasqueton, Iowa, Lujack moved with his family to Caldwell, Idaho, where he was a high school football star. After serving in the U.S. Air Force and the Washington Air National Guard, he dropped out of college in his sophomore year and landed his first radio job at KCID in Caldwell. It was there that he took on the last name of his football idol, Notre Dame quarterback Johnny Lujack.

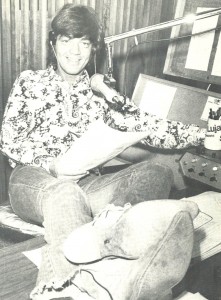

“If it hadn’t been for Elvis Presley, skin-blemish medicine and drag-strip commercials, I wonder what I’d be doing today,” he and co-writer Dan Jedlicka mused in his 1975 autobiography Superjock (which also was the on-air nickname Lujack trademarked). “Probably stocking Idaho trout streams for $400 a month and all the fish I could eat.”

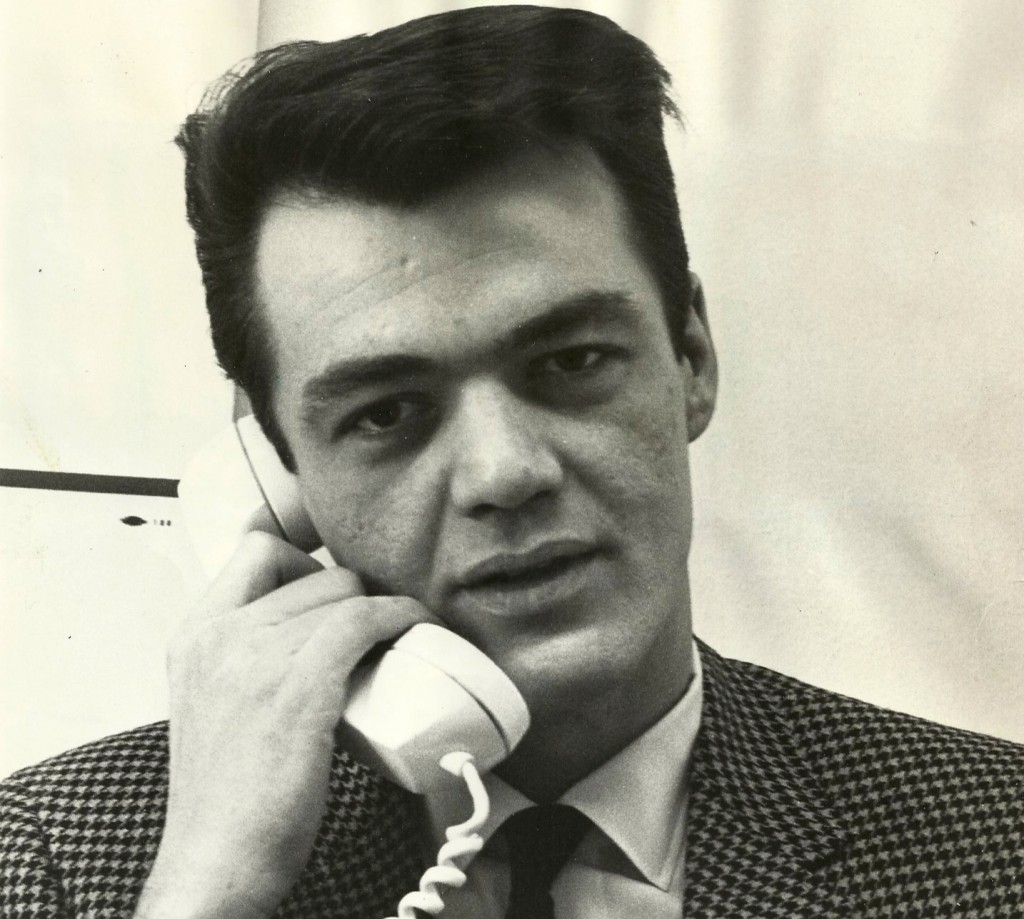

By the time he landed in Chicago as late-night personality at WCFL in 1967, Lujack had held radio jobs from Boise to Boston with several stops in between. Four months later he was on WLS, where he dominated the 50,000-watt Top 40 powerhouse for the next 20 years (except for a four-year stint back at WCFL).

A genuine original, Lujack perfected a world-weary, sarcastic style that was in stark contrast to the cheery and effervescent DJs of the era. If he was in a foul mood — which seemed to be the case most of the time — he didn’t try to hide it. Audiences found his dark, edgy humor real, relatable and unlike anything they’d ever heard on the radio before.

In moving up to mornings on WLS, he became a radio superstar of the first magnitude, dominating listenership among 18-to-49-year-olds and making millions for parent company ABC. In 1984 he was rewarded with an unprecedented 12-year, $6 million contract in order to keep him from jumping to WGN.

“It ain’t no big deal,” a typically nonchalant Lujack told me at the time. “I can honestly say — and my wife even finds this astounding — that I am not the least bit excited. Trite as it may sound, you can’t take it with you.”

Ratings declined with his ill-timed move to afternoons in 1986, and Lujack signed off from WLS a year later when ABC bought out the remainder of his contract and sent him into much-too-early retirement at age 47. He made a couple of Chicago radio comebacks on WUBT and WRLL by remote from his home in Santa Fe, but he never commanded center stage as he had in his heyday.

Practically every industry honor imaginable followed, including induction in the National Radio Hall of Fame, the National Association of Broadcasters Hall of Fame and the Illinois Broadcasters Association's Hall of Fame. He took them all in stride.

Unbeknownst to friends, Lujack had been undergoing treatment for esophageal cancer since last January, according to his wife. He insisted his illness be kept private.

“Larry wouldn’t tell anybody because he didn’t want anybody to know,” she said. “His main thing was: ‘Hey, you know what? This sucks, but 20,000 kids a day die from lack of food or lack of vaccines and everything else. So I can’t feel too sorry for myself.’ That’s where his head was the whole time.”

He even was talking about projects he was planning to do next summer before he entered hospice for his final days, she said.

In a Sun-Times interview published 30 years ago this week, a 43-year-old Lujack told me he had two main goals in life. Neither one had anything to do with radio.

“First and foremost is to make it to heaven when I die,” he said. “If I do that, then my life was a raging success, no matter what the Arbitron ratings say. My only other goal — and this is a far, far, far, far, far, far distant second — is to one day shoot 72 on the golf course.

“On the first one, I try to be a good person, an honest person and, in the crude vernacular of the rock ’n’ roll world, I don’t fuck over people. On the other thing, I hit zillions of practice balls. But if I achieve the first one, I’ll be quite satisfied even if I don’t come close to the other one.”

In addition to his wife, Lujack is survived by a son, Tony Lujack, a daughter, Linda Shirley, a stepson Taber Seguin, and two grandchildren. Another son, John Lujack, died in 1986.

There will be no services. According to his wishes, Lujack’s body will be donated to the University of New Mexico Medical Center for research.